The Ontological Argument for the Existence of God is a philosophical argument that demonstrates God’s existence from conceptuality. It originated from the writings of St. Anselm of Canterbury in the eleventh century. Anselm’s argument starts with the idea that God is the greatest possible being or “that, than which nothing greater can be conceived.” This means that God possesses all possible perfections, including omniscience, omnipotence, and perfect goodness. Anselm argued that if God only existed in the mind and not in reality, then it would be possible to conceive of something greater than God, namely, God existing in reality. Since God is the greatest possible being, Anselm concluded that God must exist in reality as well as in the mind.

Ontology is a branch of philosophy that investigates the nature of existence, what things exist, and how they relate to each other. It is concerned with the fundamental nature of reality, and seeks to answer questions such as “What is the nature of being?”, “What entities exist or can be said to exist?”, “What are the categories of existence?”, and “What is the difference between being and non-being?” Ontology can be divided into two main areas: metaphysics, which deals with the nature of reality in general, and ontology proper, which deals with the nature of specific kinds of entities, such as objects, events, processes, and properties. Often, we use the word synonymously with “definition”. Ontology seeks to tell us what things actually are.

The Ontological Argument presents a compelling case for the existence of God based on the idea of God as the greatest possible being. While the modal version of the argument is widely regarded as a strong argument, many people find it difficult to understand, and as result, unconvincing. However, for those who take the argument seriously, it can be a powerful tool for exploring the nature of God and deepening their understanding of His role in the world.

It should be noted, however, that from a Thomistic perspective, the Ontological Argument does not qualify as a demonstrative proof of God’s existence. St. Thomas Aquinas held that knowledge begins in the senses, and that one cannot infer actual existence solely from a mental concept. In his view, existence is not a property that can be contained within a definition, but rather must be demonstrated a posteriori through effects in the natural world. Thus, while Anselm’s argument is philosophically rich and worthy of attention, Aquinas would caution against treating it as a sufficient ground for belief in God’s actual existence.

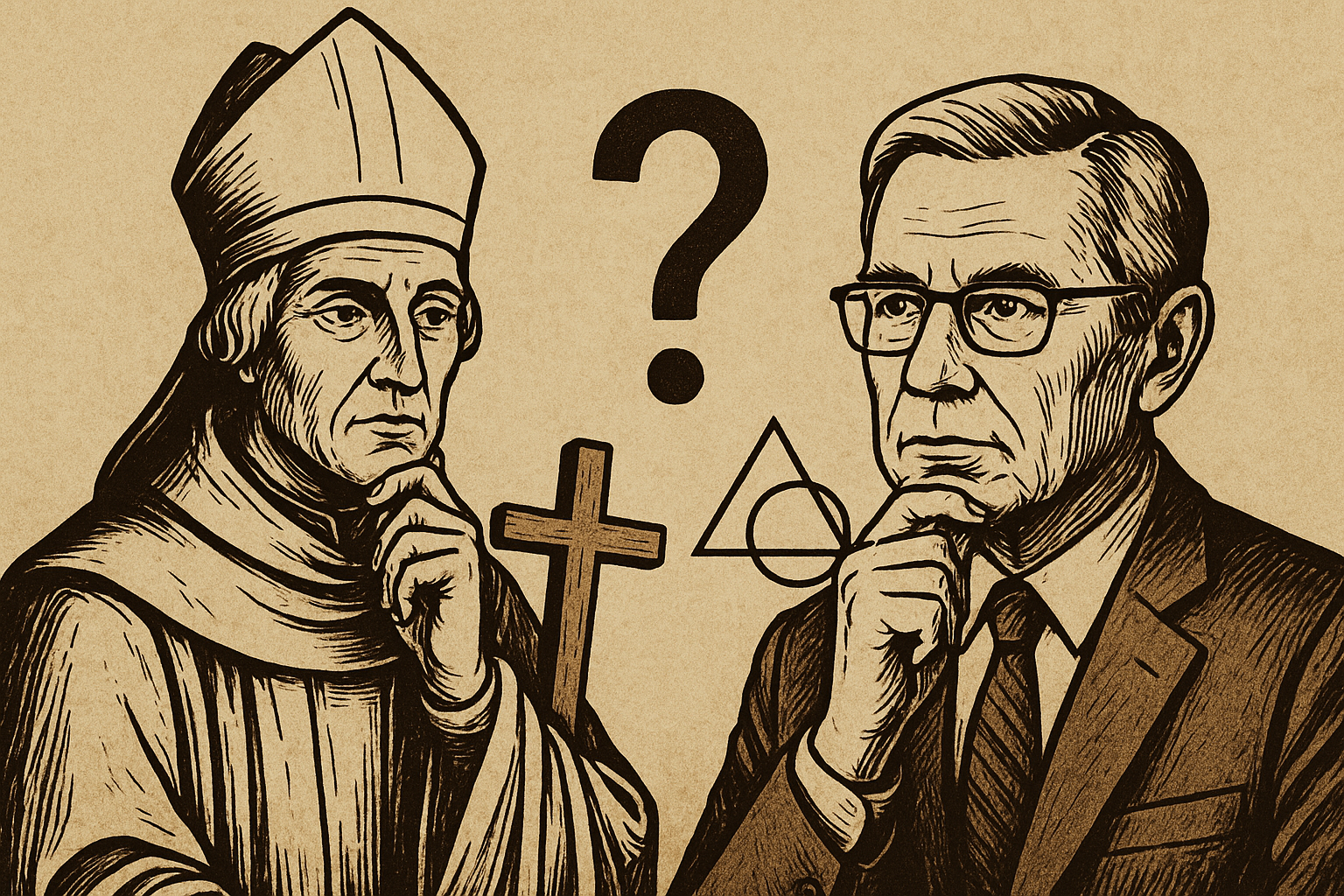

St. Anselm

St. Anselm of Canterbury was an 11th-century Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher, and theologian. Born in Italy in 1033, Anselm became a monk at the age of 27 and later served as the Archbishop of Canterbury in England. He is considered one of the most significant figures in medieval philosophy, particularly in the development of Scholasticism, a philosophical and theological system that dominated European thought during the Middle Ages.

Anselm developed the Ontological Argument for the Existence of God in his famous work Proslogion, which he wrote during his time as the abbot of the Benedictine monastery of Bec in Normandy. The Proslogion consists of two main parts: the first is a meditation on the nature of God, and the second is the Ontological Argument. Anselm developed this argument in response to a challenge by a fellow monk named Gaunilo, who argued that the existence of God could not be proven through reason alone.

Anselm’s argument begins with the idea that God is the greatest possible being, and that existence is a necessary part of being the greatest possible being. Anselm claimed that even someone who denies the existence of God must still have the concept of God in their mind, and that this concept implies that God exists in reality. He argued that the very concept of God as the greatest possible being necessitates God’s existence. The Ontological Argument has been debated by philosophers for centuries, and remains one of the most controversial and widely-discussed arguments for the existence of God.

Aquinas, while deeply respectful of Anselm’s intellect and piety, explicitly rejected this mode of reasoning. For Aquinas, we do not possess direct knowledge of God’s essence in this life, and thus cannot deduce His existence merely from a definition. Instead, Aquinas insisted that we must begin with the observable world, arguing from effects to their necessary cause. In this light, Anselm’s argument serves not as a strict proof, but as a valuable intellectual exercise that can lead the mind to contemplate the nature of divine necessity—though it falls short of establishing existence in the Thomistic sense.

Anselm’s Argument

- God is that, than which nothing greater can be conceived.

- Something that exists both in the mind and in reality is greater than something that exists only in the mind.

- If we assume that God exists only in the mind, and not in reality, it is possible to conceive of something greater than God, namely, a being that has all the qualities of God, but also exists in reality. This contradicts the original definition of God as that, than which nothing greater can be conceived.

- Therefore, God must exist in reality as well as in the mind.

Anselm’s Ontological Argument is often criticized for seemingly defining God into existence. It’s understandable to wonder how someone can prove God’s existence just by defining Him as the greatest possible being. To address this concern, it’s helpful to understand two types of definitions: stipulative and descriptive.

A stipulative definition is one that’s created for a particular discussion or argument, while a descriptive definition tries to capture the common understanding of a term. Anselm’s definition of God as the greatest possible being might sound like a stipulative definition, but it’s not. Anselm argues that the concept of God as the greatest possible being necessarily requires His existence in reality.

In other words, Anselm’s argument is not just a matter of definition. He’s not simply saying that because we define God as the greatest possible being, He must exist. Instead, Anselm’s argument is based on the idea that a being that exists in reality is greater than a being that only exists in the mind. If God is defined as the greatest possible being, then it logically follows that He must exist in reality because a being that only exists in the mind wouldn’t be the greatest possible being.

Anselm’s Ontological Argument is not based on any assumptions about God’s existence or on any empirical observations or experiences. Instead, it’s based on logical analysis of the concept of God as the greatest possible being. So, while it may still sound like Anselm is defining God into existence, his argument goes deeper than just a definition and provides a framework for exploring the nature of God and the implications of His existence.

That said, from a Thomistic perspective, the core issue lies in the assumption that existence is a perfection that can be inferred from a concept. Aquinas maintains that existence is not an attribute added to an essence but the act that actualizes it. Thus, it cannot be analytically derived from a definition, even one as elevated as that of God. Furthermore, since we cannot know God’s essence directly in this life, Aquinas would argue that it’s presumptuous to deduce His existence from an idea alone. Instead, we come to know that God exists through His effects—through motion, causality, contingency, degrees of being, and finality. Anselm’s argument may sharpen our concept of divine necessity, but it falls short of the demonstrative rigor Aquinas demands of a proof.

Alvin Plantinga

Alvin Plantinga is a prominent American philosopher and theologian who was born in 1932. He taught philosophy at Notre Dame and then at Calvin College until he retired in 2010. Plantinga’s work in philosophy is focused on the areas of epistemology, metaphysics, and philosophy of religion. He is best known for his development of the Modal Ontological Argument for the Existence of God.

Plantinga’s Modal Ontological Argument is an adaptation of Anselm’s original argument. Plantinga’s version of the argument relies on modal logic, which is a system of logic that deals with concepts like possibility, necessity, and contingency. Plantinga’s argument aims to demonstrate that it’s possible for God to exist necessarily, that is, to exist in all “possible worlds.”

In philosophy, the concept of “possible worlds” is used to explore different scenarios or situations that may or may not exist in reality, as long as they are logically coherent. Possible worlds are not alternate universes or parallel dimensions, but rather a way of imagining different ways that reality could have been, while following the laws of logic. For example, a possible world where 2+2=5 would not be logically coherent and therefore would not be considered a possible world in philosophy. Possible worlds are used to explore different philosophical questions, such as what is necessary for something to exist or what it means for something to be possible. Philosophers use the idea of possible worlds to help them think through complex questions and explore different hypothetical situations that are logically coherent.

Plantinga’s argument is contained in his book The Nature of Necessity, published in 1974. In this work, he argues that if God is defined as a being who possesses all positive properties to their maximal extent, then it’s possible that God exists necessarily. In other words, if it’s possible that God exists in any possible world, then He must exist in all possible worlds.

One key difference between Anselm’s and Plantinga’s arguments is that Anselm’s argument is based on the idea of God as the greatest possible being, while Plantinga’s argument is based on the concept of necessary existence. Another difference is that Plantinga’s argument relies on modal logic, which is a more sophisticated logical system than the one used by Anselm. Plantinga’s argument also addresses objections to Anselm’s argument, such as the objection that the concept of God is incoherent or meaningless.

From a Thomistic standpoint, however, Plantinga’s argument inherits many of the same limitations that apply to Anselm’s. While modal logic offers a refined structure, it still begins with an abstract concept and attempts to draw metaphysical conclusions without empirical grounding. Aquinas would caution that the mere possibility of a necessary being—however formally elegant—does not establish its actual existence. For Aquinas, the necessity of God’s being must be shown through effects in the natural order, not through modal constructs. Thus, while Plantinga’s version may succeed in showing the rational coherence of theism, it does not meet the criteria for a demonstrative proof in the Thomistic sense.

Plantinga’s Modal Ontological Argument

- It’s possible that a maximally great being exists.

- Plantinga asserts that it’s possible that a being who possesses all positive properties to their maximal extent exists. This being is often referred to as a maximally great being or God.

- Positive properties are attributes or qualities that are considered good or desirable. They are essential qualities for a maximally great being or God, such as being all-knowing, all-powerful, and perfectly good. These are contrasted with negative properties, which are undesirable qualities like weakness or ignorance.

- If it’s possible that a maximally great being exists, then a maximally great being exists in some possible world.

- If it’s possible for God to exist in any possible world, then He must exist in at least one possible world. This follows from the definition of possibility, which means that something is possible if it can exist in at least one possible world, that is, it doesn’t violate any of the laws of logic.

- If a maximally great being exists in some possible world, then it exists in every possible world.

- If God exists in any possible world, then He must exist in every possible world. This follows from the definition of maximal greatness, which entails that a being who possesses all positive properties to their maximal extent must be necessarily existent in all possible worlds.

- If a maximally great being exists in every possible world, then it exists in the actual world.

- If God exists in every possible world, then He must exist in the actual world. This is because the actual world is a possible world, and if God exists in all possible worlds, then He must exist in the actual world.

- Therefore, a maximally great being (i.e., God) exists in the actual world.

The modal ontological argument presented by Plantinga is a powerful philosophical argument for the existence of God, which relies on the rules of modal logic, specifically axiom S5. This axiom states that if something is possibly necessary, then it is necessary. In the context of Plantinga’s argument, this means that if God is possible, then it is necessary that He exists. The argument demonstrates that it’s possible for God to exist necessarily, that is, to exist in all possible worlds. This follows from the definition of a maximally great being, which includes necessary existence as one of its positive properties. The modal ontological argument thus uses the tools of modal logic to demonstrate the necessary existence of God.

In contrast to Anselm’s original argument, Plantinga’s Modal Ontological Argument addresses objections based on the coherence and meaningfulness of the concept of God. By using the rules of modal logic, Plantinga’s argument shows that the concept of God as a maximally great being is logically coherent and that the necessary existence of God follows logically from this concept.

From a Thomistic vantage point, however, its philosophical sophistication does not compensate for its lack of metaphysical grounding in the order of being. Aquinas would hold that necessity—when properly predicated of God—must be known through causal demonstration and not simply posited within a formal system. Possibility, in the Thomistic sense, is rooted in potency and act, not in abstract modal reasoning. While Plantinga’s argument may serve to affirm the rational intelligibility of belief in God, it cannot, for Aquinas, substitute for the empirical and metaphysical rigor demanded of a true demonstration. As such, it complements but cannot replace the Five Ways.

Common Objections

- That one could define other “maximally great” things into being.

- Anselm had a contemporary named Gaunilo who raised this objection in his work, On Behalf of the Fool. Gaunilo proposed a thought experiment involving a perfect island. He argued that if Anselm’s reasoning were sound, then one could just as easily conceive of the greatest possible island, and by the same logic, conclude that this island must exist. Anselm responded by pointing out that islands, being contingent and composed of arbitrary features, do not possess intrinsic maximums. God alone, being infinite and necessary, fits the criteria of a being than which nothing greater can be conceived. The ontological argument, then, applies only to entities whose greatness is essential and absolute—not to things like islands, which do not have built-in limits of perfection.

- That the Modal Ontological Argument relies on modal axiom S5, which begs the question.

- Modal axiom S5 is a rule in modal logic that says if something is possibly necessary, then it is necessary. Think of it like this: if it’s possible that something must happen, then it must happen. For Plantinga’s argument, this means that if it is even possible that a maximally great being exists (one whose existence is necessary), then that being must exist in reality.

- The objection raised here is that this move feels like assuming what you’re trying to prove. Critics argue that saying “It’s possible that a necessarily existing God exists” already presupposes the conclusion that God exists. Thus, if you don’t already accept the conclusion, you’re unlikely to accept the premise either, which makes the argument unpersuasive to skeptics.

- There’s also a technical distinction worth noting—between necessity de re (the necessity of a thing itself) and necessity de dicto (the necessity of a statement).

- Necessity de re refers to something that is necessarily what it is, like how water must be H2O by its very nature.

- Necessity de dicto refers to the truth of a statement, like “all bachelors are unmarried,” which is necessarily true by the definition of the terms.

- Critics sometimes conflate these. Plantinga’s argument makes a claim about the possible truth of a statement (de dicto)—that “a maximally great being exists” is possibly true. It is not merely asserting that such a being necessarily exists in every possible world, which would be circular.

- That Alvin Plantinga doesn’t believe his Modal Ontological Argument is a good argument.

- Skeptics often quote Plantinga’s own cautious language to dismiss the argument. In The Nature of Necessity, he writes: “It must be conceded, however, that Argument A is not a successful piece of natural theology. For the latter typically draws its premises from the stock of propositions accepted by nearly every sane man, or perhaps nearly every rational man … Hence, our verdict on these reformulated versions of St. Anselm’s argument must be as follows. They cannot, perhaps, be said to prove or establish their conclusion.”

- However, they frequently omit the next line: “But since it is rational to accept their central premises, they do show that it is rational to accept that conclusion. And perhaps that is all that can be expected of any such argument.”1Plantinga, A. (1974). God and necessity. In The nature of necessity (pp. 219–221). Oxford University Press. Plantinga’s point is nuanced. He does not reject the argument’s logic, but he recognizes that its premises are not universally compelling. For this reason, he does not consider it a strict proof of God’s existence, but a rationally coherent argument that supports belief in God for those who accept its initial assumptions.

- From a Thomistic perspective, this underscores the difference between plausibility and demonstration. The ontological argument may serve a useful role within a broader cumulative case, but it cannot substitute for metaphysical demonstration grounded in reality. Again, for Aquinas, arguments for God’s existence must begin with the world of sense experience and reason upward—not from a mere possibility within abstract logic.

Footnotes

- 1Plantinga, A. (1974). God and necessity. In The nature of necessity (pp. 219–221). Oxford University Press.

This is a really great argument. I can’t think of any counters.